Quick question: when you travel, do you prefer nonstop flights, or flying through a hub airport somewhere? How about when you have a bunch of things to do around town on a Saturday morning: do you come home after every errand, or do you go directly from one location to the next?

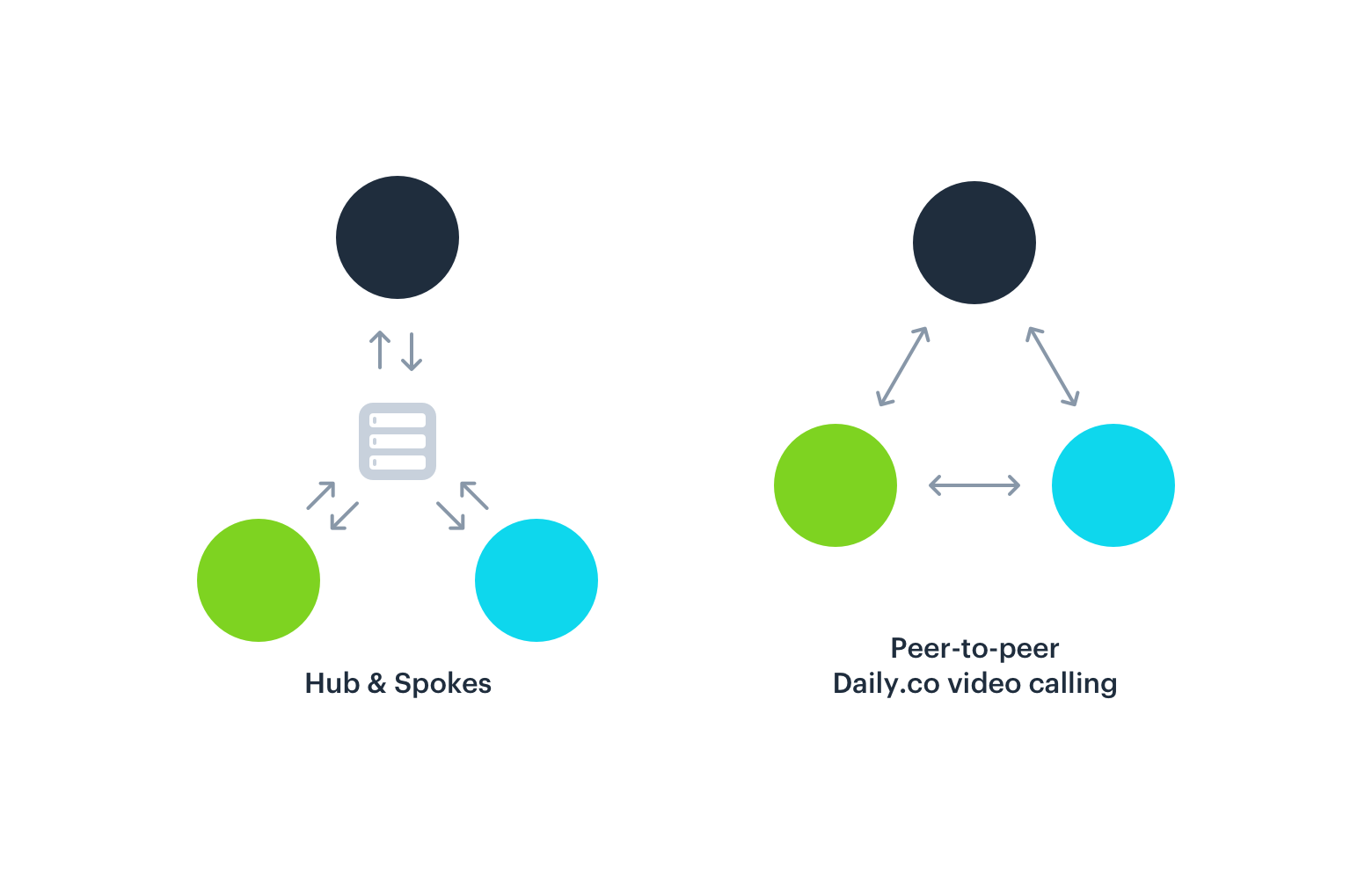

Me, too! I like going directly from place to place, whenever possible. And it turns out that moving data around the Internet is just a little bit like driving or flying. Sending data directly from one computer to another is faster than sending stuff through centralized “hub” computers in the cloud.

People like me, who love network engineering, call this peer-to-peer networking (P2P).

Most of the time, when you do a video call using a program like Skype, your data is not routed peer to peer. All your video and audio go through Google’s or Microsoft’s servers. Back a few years ago, when our computers had a lot less processing power, and bandwidth was pretty limited, that was helpful. But these days it’s actually not so great.

Daily uses a “Peer-to-Peer” model. You don’t go through a server. Instead, each participant talks directly with each other participant.

I’ve been obsessed with digital video for a long time. For the last few years I’ve been building various things on top of a new standard called WebRTC. WebRTC provides a rock solid, reliable way to send streams of data (like video and audio) directly between any two computers on the Internet.

My company Daily is a developer platform for video. Our APIs make it much faster to build with real-time video. A developer can start quickly, adding video calls to any site or app with a couple lines of code. Our front-end libraries and REST API let developers customize layout and controls.

The Daily platform leverages peer-to-peer networking and WebRTC to deliver high quality video over real-world Internet connections, across browsers and devices. We work with customers in every market, across the world, so it's key we design and test our calls to work for a call participant, wherever they are!

Here’s how a Daily video call works

Below some of these diagrams are technical details, in case you’re interested.

Step 1: When you want to join a Daily call, you click on a Daily meeting link, which looks something like this …

https://you.daily.co/p2p

(You get your own custom subdomain, with unlimited video call rooms, with Daily.)

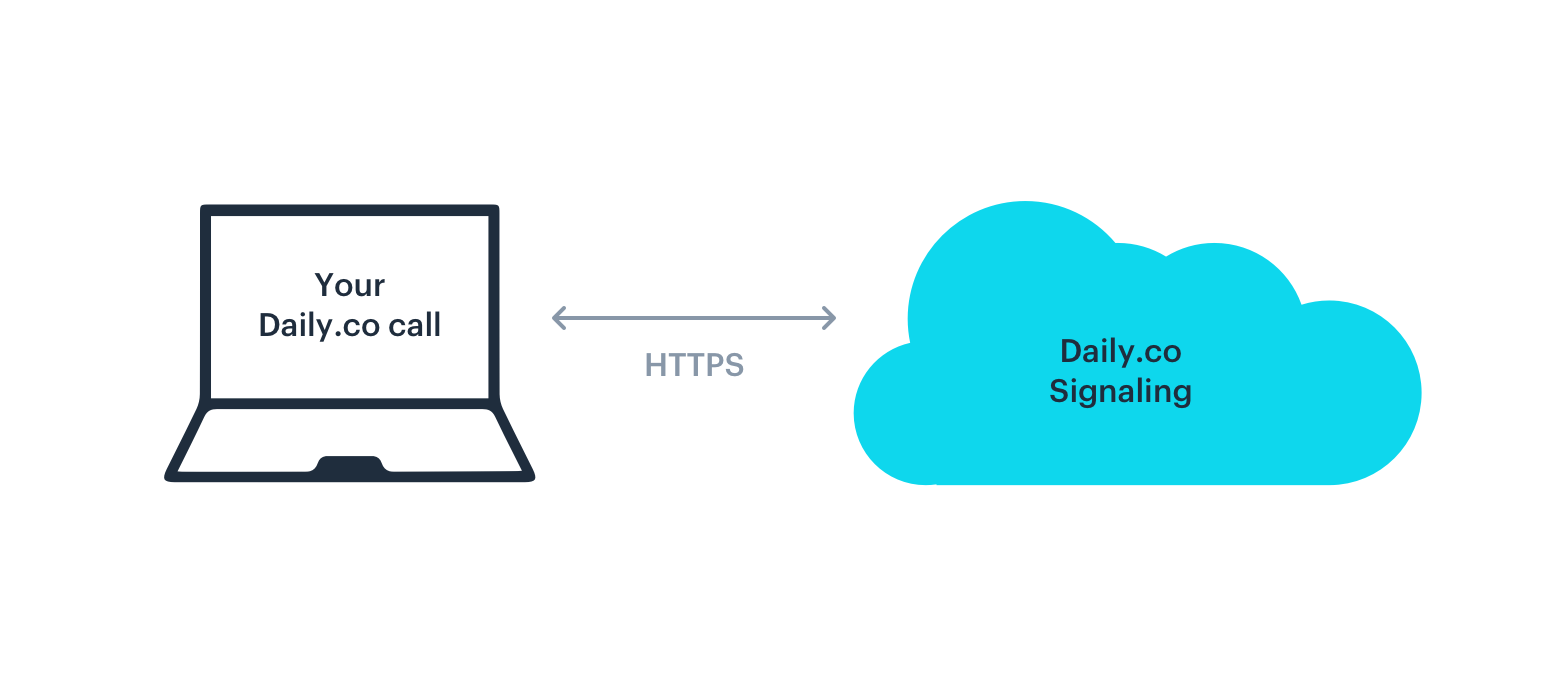

Step 2: We maintain some servers in the cloud that we use for signaling, for setting up and managing each call. Your web browser says to our signaling servers: “Hey, I want to join this call, please tell anyone else in this call a little bit about me, and how to find me on the Internet.” Keep in mind that you’re talking to our signaling server just to set up the call.

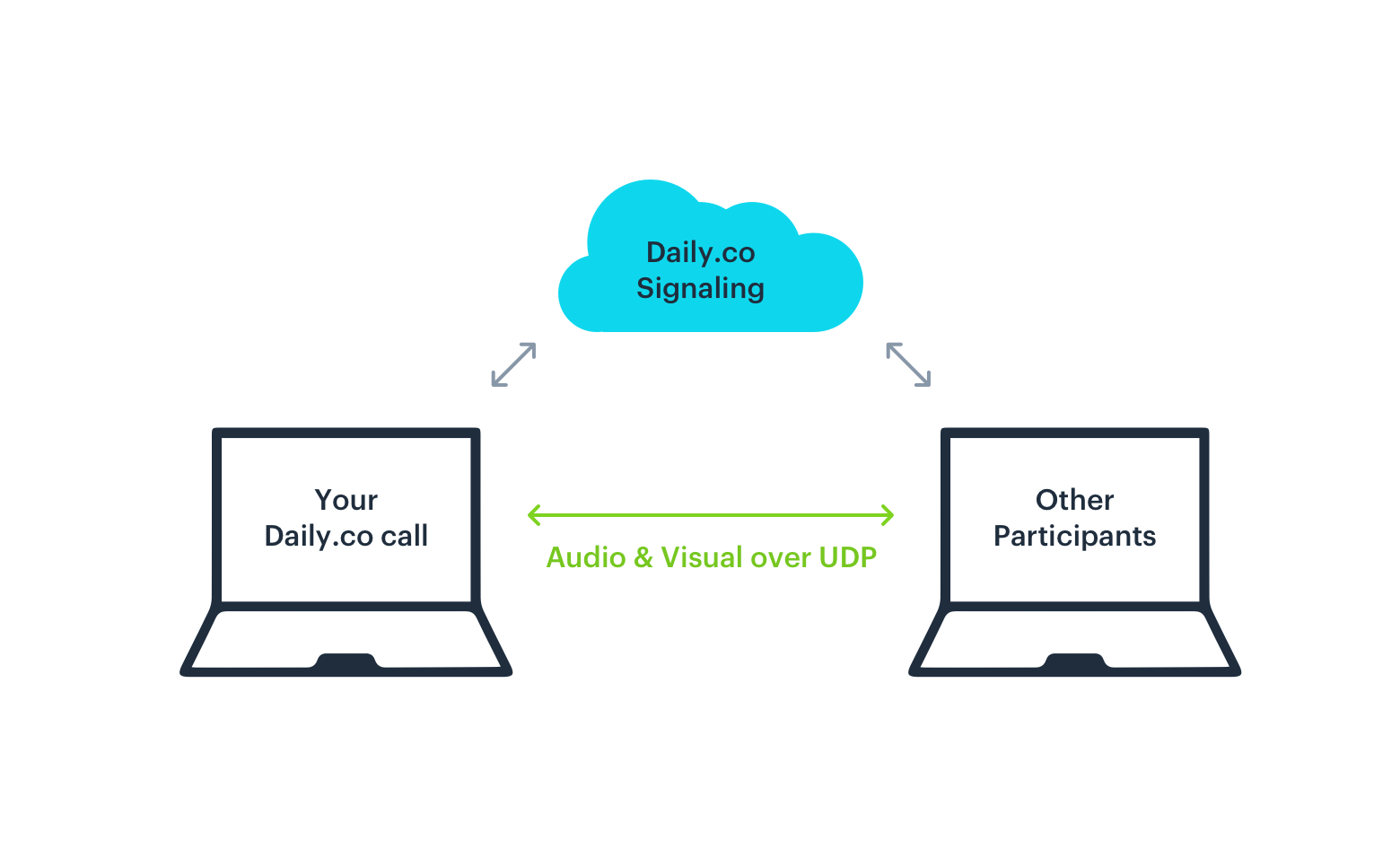

Step 3: The other participants also are talking to Daily’s signaling server, to set up the call on their end. Like you, they’re telling the signaling server a little bit about themselves, like where you can find them:

- Detail: The information you’re exchanging to set up a call is mostly in the form of SDP records

Step 4: Daily’s signaling servers have passed on relevant info from call participants. Now, your Daily browser can connect directly to each of the other browsers on the call. You send your video and audio, separately, to each peer.

- Detail: You still keep a background connection with the Daily signaling server. It lets you know, for example, when a new colleague wants to join the meeting. But the amount of data through the signaling server is small. The key data, which is your actual video and audio, is content you’re exchanging directly with each other participant.

Voila! Because you are directly connected to each person you are talking to, each video and audio stream is as high-quality, and as low-latency, as possible. As an added benefit, you know for sure that your video and audio are secure — nobody else can see or hear them. The data is encrypted and nobody except the sender and receiver of each stream have the encryption keys.

Group calls with P2P

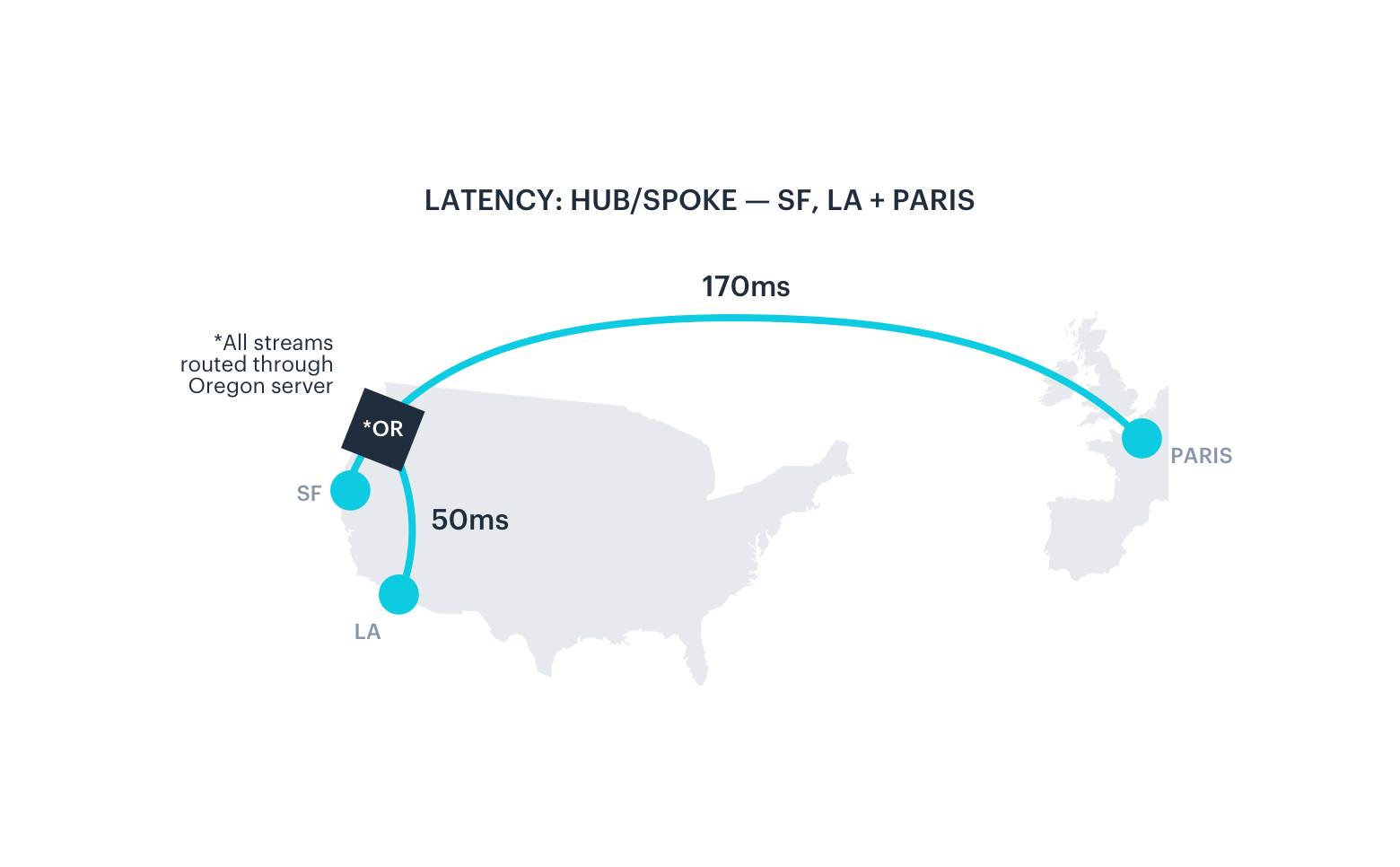

Let’s compare this peer-to-peer video call with a more traditional call that is routed through a server. This server is in, for example, Oregon. (There are a lot of data centers in Oregon.)

Sending an Internet packet from San Francisco to Los Angeles usually takes about 20 milliseconds. (That’s 1/50th of a second. Fast enough that you won’t notice the delay.) Sending a packet from San Francisco to Paris, though, typically takes 150 milliseconds or more. (About 1/7th of a second. That delay is noticeable, but it’s not too bad.)

However, if you have to send all your audio and video through the server in Oregon, you introduce more delay. Every packet has to travel two network legs. (Plus the server introduces some delay, but we’ll ignore that for the moment.)

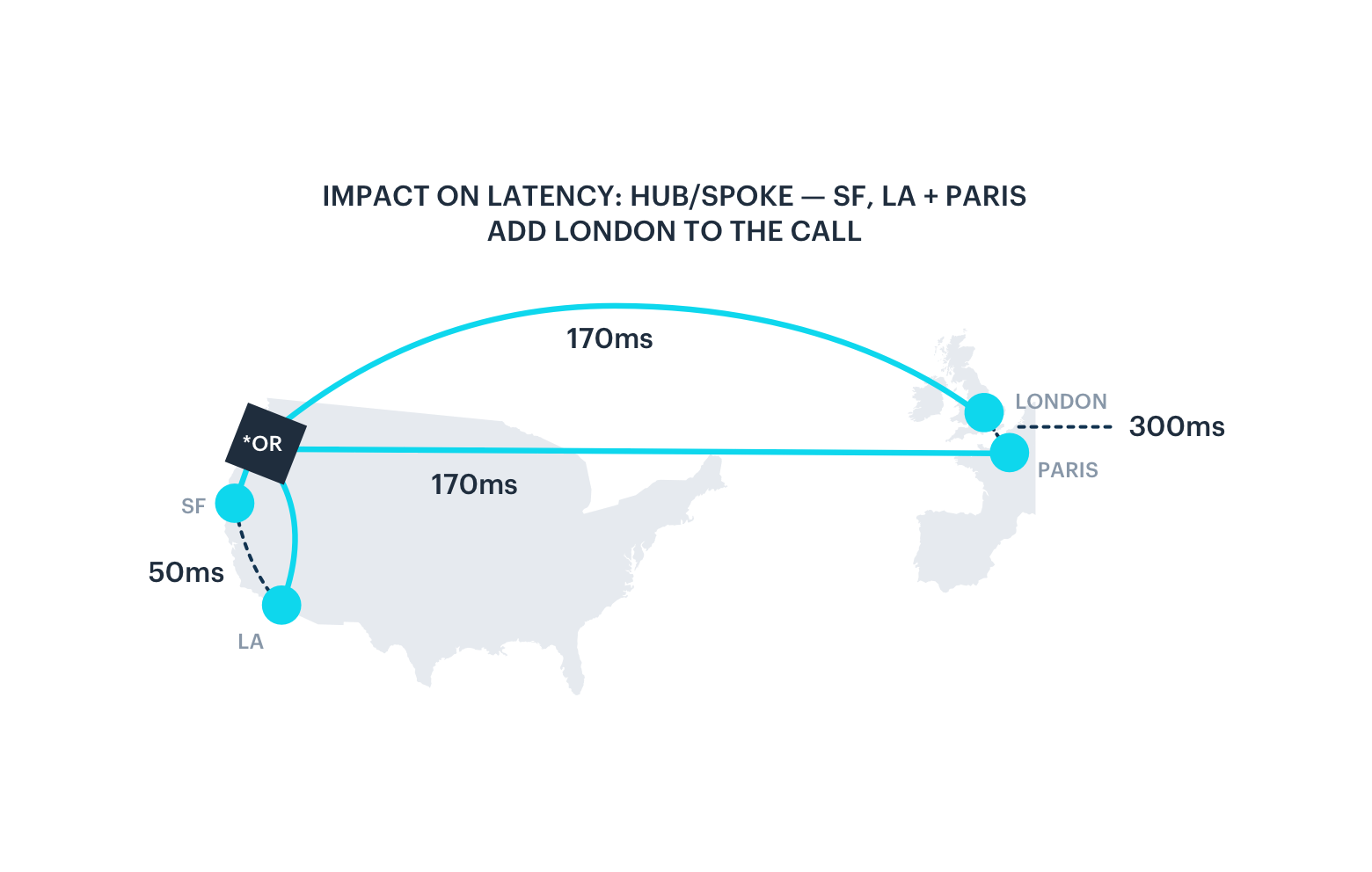

But wait, it gets much worse! Let’s add someone in London to the call. Now data going from Paris to London is very, very slow (because it has to go to Oregon and back).

- There’s nowhere in the world that we can put our server and have this call be a good experience for everyone.

In contrast, the peer-to-peer call works pretty well for everyone. Each link is as fast as possible.

P2P: Pros & Cons

The advantages of pure peer-to-peer are significant, which is why the Daily architecture is built on P2P. Because each participant connects directly to every other participant, each video stream is as high- quality, and as low-latency, as possible. This is noticeable to end users. And it is particularly apparent on international calls.

But pure P2P only scales to a certain point.

Daily calls can have a maximum of 200 participants. Most people don’t have enough bandwidth available to send 200 high-quality video streams to each of the other people in a 200-person call.

And sometimes people who need to join a call are behind network firewalls that don’t allow P2P connections.

Falling back to relaying where necessary

We’ve done a lot of logging and analysis of call quality, and we’ve found that when there are more than 5 people in a peer-to-peer video call, it’s very common for network bandwidth to start to become an issue.

So when Daily calls get above a certain size we switch everyone in the call over to using relayed, rather than peer-to-peer, connections. This is all done behind the scenes, and most of the time you won’t notice this switch-over happening.

Additionally, on some networks, all P2P connection attempts will fail. Firewalls at large enterprises are sometimes configured to block most or all UDP traffic. We see this happen for fewer than 1% of all Daily calls, but we want calls to “always work.” So it’s critical to handle this situation.

We have two fallbacks in place for networks on which peer-to-peer connections aren’t possible. First, we try to send UDP traffic through our servers, rather than peer-to-peer. That often works. But if it doesn’t, we switch over to using TCP tunneling to send the video and audio. Again, through our servers. And that almost always works. In fact, we’ve never seen a failure in real world testing.

Of course, routing video and audio through our servers is what we just tried to explain, using all those diagrams above, you don’t want to do. But — and this is important — we only route traffic through our servers when we have to. We can detect that network bandwidth or firewalls are an issue, and choose the best connection type in real time. If the problem is a firewall, we can relay on a per-connection basis. We don’t have to do it for everyone on a call.

Finally, it’s important to note that video being relayed is still encrypted. It’s not encrypted end to end (that’s not possible). But it is encrypted to and from our servers using exactly the same encryption standards as we use for all of your peer-to-peer connections.

Adjusting video quality in real time

While a call is ongoing, we can adjust the video quality to match the bandwidth that’s available for each peer-to-peer connection.

For good video and audio quality, a Daily participant needs to have 200 kb/s of bandwidth available both upstream and downstream for each peer that it is communicating with. So, for a four-way call, each location needs to have at least 600 kb/s of “upstream” bandwidth available to send video/audio, and 600 kb/s of “downstream” available to receive video/audio.

The peer-to-peer architecture makes it possible to adjust the video quality for each link independently. In the example above, the participants in London and Paris would see very high quality video for each other, and somewhat lower quality from their colleagues in the United States. In contrast, everyone would see lower quality video with an old-style “cloud” video architecture.

Protocols

If you’re interested in learning more about the protocols that we use to set up calls and send audio and video, here are links to the standards that we’ve mentioned in this overview.

- WebRTC: https://www.w3.org/TR/webrtc/

- STUN: https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7064

- ICE: https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc5245

- TURN: https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc5766

Thanks for learning more about how we built Daily. We're curious to hear how your experience is, whether you're p2p, or on the cloud with our large meetings. Let us know if you have any questions about call quality!